Writing good rulebooks is one of the most challenging aspects of making a board game. Let’s face it: learning a game from a rulebook sucks. No matter how good you are at parsing written instructions, complex systems are simply hard to explain with text and images.

I am in no way a rulebook writing master, but the Resonym team has written rulebooks for around 10 games now, and we’ve been getting better and better each time. Tom Vasel of the Dice Tower said of the Mechanica rulebook: “Really, really nicely done. One of the better written rulebooks I’ve ever seen.”

First some general structure tips, then some of the common big picture challenges we encounter when writing rulebooks, and some solutions!

General Structure

Our rulebooks usually follow the same general structure:

-

-

- Story – set the scene for the players.

- Goal – it helps players to know what they’re trying to do as they read about how to do it.

- Game End – knowing how the game is going to end is often useful up front.

- Components – if you don’t show pictures of the components and name them, players will often get confused about which component is which. Without a components guide players might not realize if they are missing pieces.

- Setup – walk players through a list of setup steps, and have a diagram!

- Gameplay – explain what happens on players’ turns. This section differs wildly from game to game.

- Ending the Game – tell players what to do when the game is over.

-

In addition to this structure, here are some things to keep in mind when writing your rulebook:

-

- Examples – Examples complement text explanations, so include them whenever there’s a particularly tricky rules section.

- Diagrams – Diagrams are even better than examples when you have space for them!

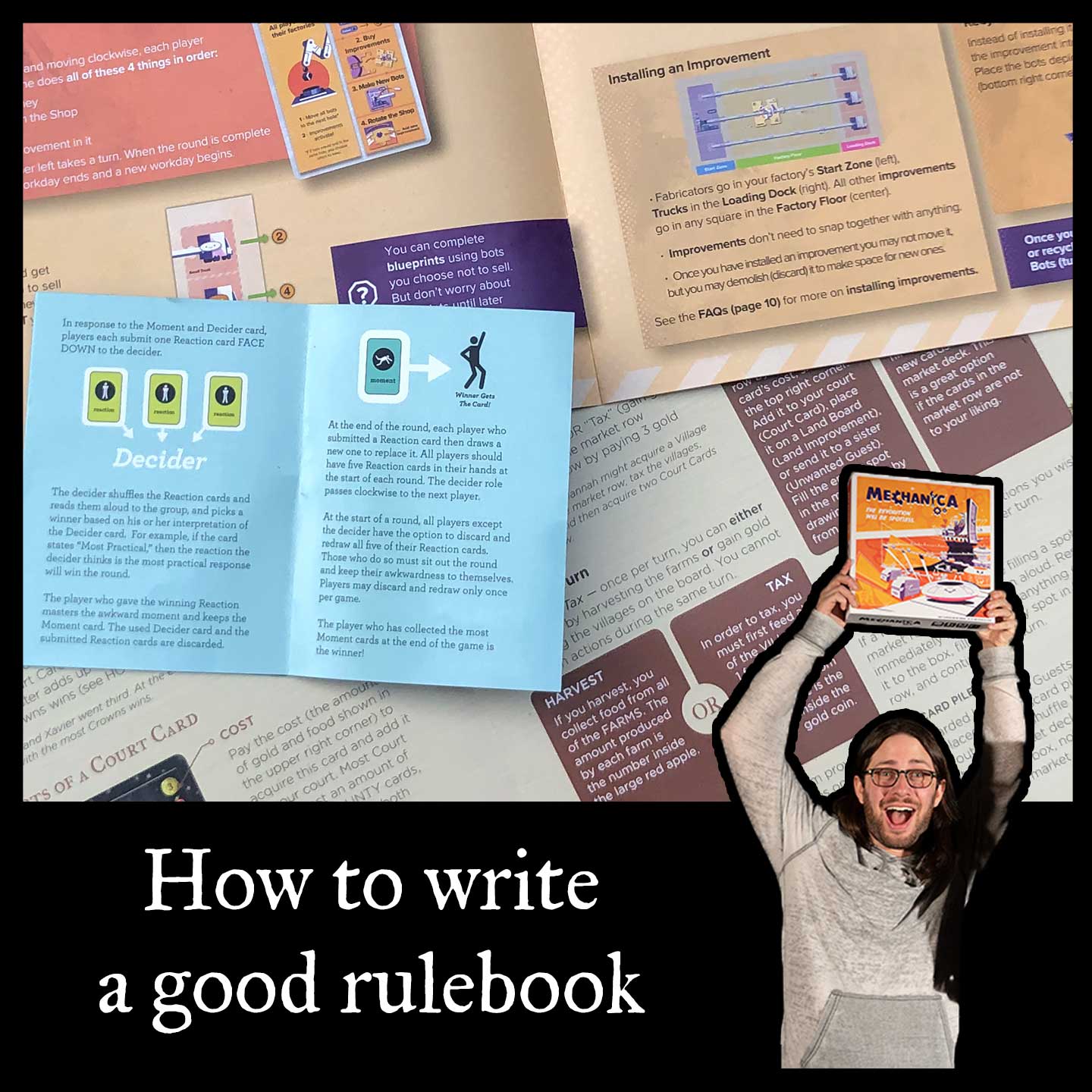

- Anatomy – If you have cards or components with lots of information printed on them, you may want to include an “anatomy” diagram that labels the different types of information of the component (e.g. cost, type, effect, strength, etc.).

- FAQs – FAQ sections can be useful if you have room to include them.

- Second Person – Give players direct instructions using second person whenever possible. For example, “Shuffle the deck and lay out 5 cards in a row face up.”

- Singular “They” – When second person is impossible, use the singular “they.” For example, “Each player draws 6 cards to form their hand.”

- Pronouns – Resonym never defaults to he/him pronouns in rulebooks, although occasionally we’ll use she/her pronouns instead of the singular “they.” Cis men make up a large proportion of the gaming community and we don’t need to alienate others in order to make men feel more welcome.

- Icons – In-text icons can be very useful for making text easier to skim.

- Capitalization – You can capitalize some keywords and phrases, but don’t go overboard. If you have too much capitalization, it all blends together and is useless.

- Extra Room – If you’re self publishing, give yourself more room (an extra 2-4 pages) than you think you need. There are always useful ways to fill space, even if it’s only having your characters pop in to help reinforce the story, but it’s hard to make more space when you’ve already laid out your rulebook.

- Spreads – Remember that books come in spreads of 4 pages, so your page count (including the front and back cover) must be divisible by 4. Use facing pages to your advantage. For example, if your component list and setup sections don’t fit on the same page, make them facing pages so players don’t need to keep turning back a page to figure out what a “Guest Card” is.

Quickstart Guide vs. Reference Materials

The single biggest challenge in writing rulebooks is that players always need them to be two things at once: a quickstart guide for new players learning the game and a logically organized reference for experienced players with a specific question.

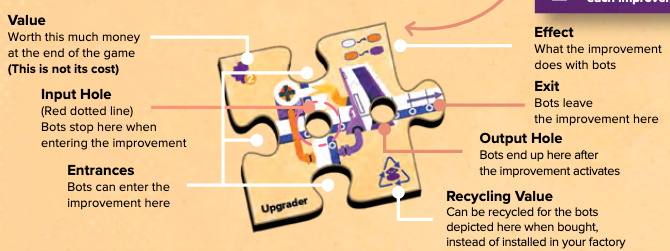

The problem that our team runs into over and over again, is when a rule is not relevant until later in the game, but logically shouldn’t be moved later in the rulebook. A great example is the “Play a Guest” action in Surrealist Dinner Party. Here’s the text from that section:

“Play a Guest” is the very first action players will take on their turns. There are two parts to the action: “Seat a Guest” and “Send a Guest Home.” New players will use the “Seat a Guest” part on their first turn to play a card from their hand. They won’t need to “Send a Guest Home” until later in the game when they’ve filled up their 3 spots for guests.

But later in the game it becomes essential that you can send a guest home when you’re done with them and want to make room for a new guest! New players get tripped up over the paragraph that is not relevant to their current game state, while experienced players will immediately flip to this section of the rulebook if they want to review how the “Send a Guest Home” subaction works…

We want to move the paragraph because it confuses new players, but if we do, experienced players won’t be able to find it. What’s a rulebook writer to do?

Solution 1: Separate Quickstart Guide

The best way to learn a board game is from someone who knows how to play. Why? It’s because someone who knows how to play can flip over literally any card in the game and show examples of gameplay using that card.

Using some sneaky tricks, rulebook writers can make separate quickstart guides that approximate a player teaching you how to play! Fog of Love, for example, has a great quickstart setup: the game instructs players not to shuffle the decks on their first play. That way, the quickstart guide knows exactly which cards each player drew, and can walk them through their first game’s choices!

When this can be achieved, it’s a fantastic way to solve the problem. You have all of your reference materials in your actual rulebook for the players to look up, but for learning you use the quickstart guide.

The drawbacks of this approach are that it’s more expensive to have multiple booklets (so you’ll see it more in large and more expensive games than smaller ones), and that it’s only fully feasible for some games. For example, Fog of Love can pull off a fully featured quickstart guide because it’s a two player game and the rulebook writers can know for sure what cards are available to each player throughout the first game.

Solution 2: Shift Focus Away from the Unnecessary Info

In Surrealist Dinner Party, we ultimately made a callout box encouraging new players to ignore the “Send a Guest Home” option for now. This works to a degree, but there are other ways to get players to skip text you don’t want them to immediately read.

The “Advanced Modes” in Surrealist Dinner Party are a great example! The last page of the rulebook contains several advanced play modes that we want players to eventually add into the game, but to not bother with for their first few games. So we flipped that entire section upside down as an experiment:

…and immediately playtesters stopped accidentally reading it! Going forward, we’re going to consider flipping more text over—important text that we don’t want new players to read for their first game can be flipped to make it impossible to read unless you’re trying to. We used some similar (albeit less weird) tactics in the Mechanica rulebook: we faded text in several places to make players have to concentrate in order to read it.

This solution can be cool but it can also make your rulebooks look strange at a glance! Fortunately, Surrealist Dinner Party can have a surreal rulebook.

The Chicken-Egg Problem

Games are systems. Each part of the system relates to several other parts of the system in a loop. One of the challenges of writing rulebooks, is that even the simplest game cannot be described fully linearly. At some point, you’re going to have to reference a concept you haven’t defined yet. This is the chicken-egg problem of rulebook design.

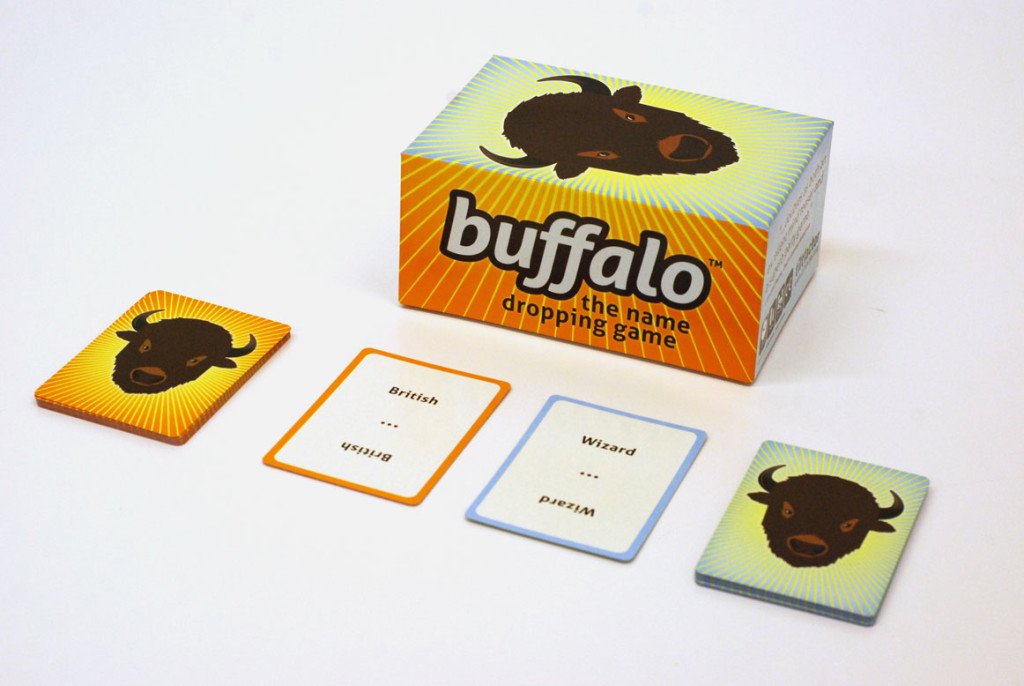

Our game Buffalo: the Name Dropping Game is an extremely simple example. Here’s how it’s played:

You flip over a noun card and an adjective card in the center of the table. All players race to shout out the name of a real person or fictional character that matches two (or more) of the cards on the table—the first player to successfully do so takes the cards they matched. For example, if the cards on the table were “Female” and “Scientist,” I could name Ada Lovelace, and take those cards.

Whenever there are zero or one word cards left on the table, add a new card in from each deck. Whenever the group cannot name someone, add a new card in from each deck.

This will often result in there being more than 2 word cards on the table at once! When that’s the case, you can match any 2 or more of those cards. Whichever cards you match you get to keep.

There are also Buffalo cards. These don’t count as word cards, but whenever you make a match with a Buffalo card on the table, you take all the cards, not just the ones you matched (including the Buffalo card).

Even with a game this simple, you can see that I had to introduce concepts early that I wasn’t able to explain until later. For example, in the first paragraph I said “that matches two (or more) of the cards.” But at that point, I hadn’t explained how you could get more than two cards on the table at once. I also said “Whenever there are zero or one word cards left,” before I had introduced that there were non-word cards (the Buffalo cards).

I could have flipped the explanation and removed the concept of “word cards” from the second paragraph, and then later said “Buffalo cards don’t count toward the cards left on the table, so if there’s a Buffalo card and a single other card on the table, you flip a new card from each deck.” This would avoid introducing a concept I hadn’t defined, but then the sentence “Whenever there are zero or one word cards left on the table, add a new card in from each deck” is technically a lie.

This challenge crops up again and again in rulebooks, and the best solution we’ve come up with is to figure out which way is less ultimately less confusing. Sorry! No tricks for solving this one.

Playtesting Is Painful

Normal playtests are fun for your players, because your game is fun, and fun for you because you get to help them have fun. Rulebook playtests (also known as “blind playtests”)—where you seat a player down in front of your rulebook and have them play without your guidance—on the other hand, are agonizing.

In rulebook playtests, your players have to learn the game from the rulebook, which is the least fun part of playing a new game. In addition, you have to sit still and watch them fail… and many designers have a really hard time restraining themselves from intervening. Here are some little tips to help your rulebook playtests go smoothly, but also let you make your rulebooks the best they can be.

Tip 1: Warn Your Playtesters

Make sure your playtesters know that this isn’t a normal playtest: “In this playtest you’re going to be reading the rulebook and learning how to play. Reading rulebooks can be hard. We’re here to find the parts that are confusing, so if you’re confused at any point, let me know—it’s not your fault, it’s ours. I’ll write down the confusion—I won’t be able to help you with it, but I’ll fix it in the future.”

After the time my wife broke down in tears during a rulebook test, I always make sure playtesters know what they’re getting into.

Tip 2: Test With Nongamers

Rulebook testing with experienced board gamers is comparatively easy, since they often already know how to read rulebooks. You should seek out folks who don’t read rulebooks often—your family, your nongaming friends, anyone who you can convince to test—because these playtests are the ones that will make your rulebook awesome. If your rulebook can teach your grandma how to play your game, then it can teach anyone.

Tip 3: Play Dumb

In an ideal world, you’d be watching your playtesters from behind a one-way mirror. Since most of us don’t have that luxury (especially during COVID), we often will bring in a single player to playtest, and have them teach us how to play the game.

As you test you will quickly learn the problem areas in your rulebook: which rules trip players up. The real challenge is figuring out why your phrasings and formatting are hard to understand, and how to fix them.

Whenever possible make your playtester do all of the heavy lifting. The most common phrase I use in rulebook playtests that I am running and participating in is “What do I do now?” I use this at nearly every juncture, particularly right before a rule that commonly trips players up. It’s easy to accidentally do the correct action. Instead I try to interrupt myself, and ask the playtester “What do I do now?” Another one of my favorite phrases is “How should I make that decision?”

You won’t always want to ask “What do I do now?” Another great tactic is to simply do it wrong. If you saw a player misunderstand a rule in a previous playthrough of the game, a great way to see if that’s a common misunderstanding is to enact it yourself, and see if your playtester catches you!

Tip 4: DO NOT HELP THEM

It’s really, really tempting to step in and save your players when they inevitably make mistakes. And will helping them with this one little thing really hurt? You already know that there’s a problem in that paragraph of the rules so you’ll fix it! In the meantime why make your players suffer?

Unfortunately, if you swoop in to save your players from mistakes, they become reliant on you. They learn that they don’t need to think too hard about whether the rules work this way or that way; they just need to choose one and then look at you to see if you correct them.

In Surrealist Dinner Party, you put out a number of Food tokens on the table each round. Once those tokens have all been taken, you put out another set. In one rulebook test, the players put all the tokens for the entire game out at the start, leaving this gigantic ugly pile of tokens. And I just let them play that way. The game was significantly less fun, but it wasn’t worth undermining the playtest.

The only time you should step in is when a player’s interpretation of the rules will invalidate the rest of the playtest. This happens when their current misinterpretation won’t let you see if the player properly understands a different important (commonly misunderstood) part of the game. For example, in one Surrealist Dinner Party test, the player missed the rule that you can only have 3 guests out at once. Because of this misinterpretation, they would never have needed to send a guest home. The rule that you can send a guest home and then seat a new guest in the same turn was overlooked by players in the past few tests. Since this player didn’t notice the guest limit, they would never have needed to send guests home and I would never have had a chance to see if the revisions to the rules made the “send a guest home and then seat a guest in the same turn” rule more clear.

The only time you should step in is when a player’s interpretation of the rules will invalidate the rest of the playtest. This happens when their current misinterpretation won’t let you see if the player properly understands a different important (commonly misunderstood) part of the game. For example, in one Surrealist Dinner Party test, the player missed the rule that you can only have 3 guests out at once. Because of this misinterpretation, they would never have needed to send a guest home. The rule that you can send a guest home and then seat a new guest in the same turn was overlooked by players in the past few tests. Since this player didn’t notice the guest limit, they would never have needed to send guests home and I would never have had a chance to see if the revisions to the rules made the “send a guest home and then seat a guest in the same turn” rule more clear.

So in this case, I waited a few turns and then corrected them. Then I made a big note to myself that I corrected them. If I don’t make such a note, I find it very easy to forget that I corrected the player and forget that they had a confusion about that rule.

Okay that’s my monster rant on rulebook writing! Hopefully you picked up some playtesting tricks and ideas for what to look out for when you’re writing your next rulebook. If you want to chat with the Resonym team about game design (or just hang out), come join our Discord server at resonym.com/discord

Until next time with more design and publishing tips!